Distance, dispassion and the remaking of Australian History

Anna Clark could have titled her book “Remaking Australian History”, for that is its narrative arc.

She celebrates a change in the stories Australians can tell of their nation: from a heroic tale of white male achievements (populating and fructifying an empty land, establishing a variant of western civilisation) to stories that acknowledge the continent’s ancient human past, the brutalities of colonisation, and the diversity and increasing self-doubts of the usurping newcomers.

Clark grew into her profession (teaching and writing history in universities) as scholarship was establishing this new narrative, and her book names and honours many of those now responsible for sustaining and propagating it.

She has much to say about History – the uppercase “H” signifying “the subject that’s taught in schools and universities, has established professional associations and qualifications”. What makes it important to her is that History is a major source of historical consciousness – a “sense of the past”. How well or how badly has History shaped Australians’ historical consciousness? Could History do this culture-forming job better?

Clark intends her history of making Australian History to be an “analysis of the structure, function and ethics of the discipline itself”. She has much to say about History’s aspiration to “objectivity”, pointing out its inescapable complicity with emotions, its duty of ethical formation, its permeability to nation-making, and its changing claims to cognitive authority.

Her grounds for evaluating History are primarily civic or ethical. Twice she decries its “hypocrisy”. Each time it is for archiving the Indigenous presence, but leaving Indigenous people out of the national narrative. She faults History for its long silence (c.1890s to 1970s) about Australia as a violent settler-colonial project and its partiality to the colonists’ most self-admiring accounts.

As Clark observes, one of the abiding problems of History as a discipline all over the world is that, for all its scholarly objectivity, it is porous to the ambient, strident noise of nation-building. She acknowledges that her own critique and celebration of Australian History is no less a product of a prominent concern of our times: how to find a just relationship with Indigenous Australians.

Clark grew into her profession (teaching and writing history in universities) as scholarship was establishing this new narrative, and her book names and honours many of those now responsible for sustaining and propagating it.

She has much to say about History – the uppercase “H” signifying “the subject that’s taught in schools and universities, has established professional associations and qualifications”. What makes it important to her is that History is a major source of historical consciousness – a “sense of the past”. How well or how badly has History shaped Australians’ historical consciousness? Could History do this culture-forming job better?

Anna Clark. Penguin Books Australia

Clark intends her history of making Australian History to be an “analysis of the structure, function and ethics of the discipline itself”. She has much to say about History’s aspiration to “objectivity”, pointing out its inescapable complicity with emotions, its duty of ethical formation, its permeability to nation-making, and its changing claims to cognitive authority.

Her grounds for evaluating History are primarily civic or ethical. Twice she decries its “hypocrisy”. Each time it is for archiving the Indigenous presence, but leaving Indigenous people out of the national narrative. She faults History for its long silence (c.1890s to 1970s) about Australia as a violent settler-colonial project and its partiality to the colonists’ most self-admiring accounts.

As Clark observes, one of the abiding problems of History as a discipline all over the world is that, for all its scholarly objectivity, it is porous to the ambient, strident noise of nation-building. She acknowledges that her own critique and celebration of Australian History is no less a product of a prominent concern of our times: how to find a just relationship with Indigenous Australians.

While certain official narratives and histories did their best to position ‘The Convicts’ in the distant past, or to avoid them altogether, a new school of politically radical, working-class histories did the opposite.

Further revisions (Marxist, feminist) of these revisions have followed since 1970.

Clark then points to a moment – the turn of the 20th century – when there were rival perspectives on Australia’s history: “Unifying secular national sentiment rubbed uneasily against regional, radical republican and sectarian religious identities.”

Sectarian religious identities did not go away. In 1946, John Murtagh’s book Australia: The Catholic Chapter depicted our history as an instance of “the crisis of liberalism”, as seen from the perspective of the Catholic Social Movement.

Now, multiculturalism is probably encouraging Islamic and other perspectives on Australian history. Clark is open to the effects on historical scholarship of Australia remaining a diversely religious nation; she hails Samia Khatun’s groundbreaking history of South Asian migration Australianama (2018).

Rather than explore these possibilities, however, Clark keeps her history of Australian History focused on the “secular national sentiment” that flourished with the formation of free, compulsory and secular education systems and became dominant in the Humanities disciplines, including History.

Clark established her academic reputation with studies of contemporary practices of school history teaching. History, she argues, became central to the moral education of Australians the more moral education came to be mediated by the state, rather than by the church. Nationhood needs a past, and Clark gives the label “Federation historiography” to the morally fortifying past that historians began to supply in the 1890s.

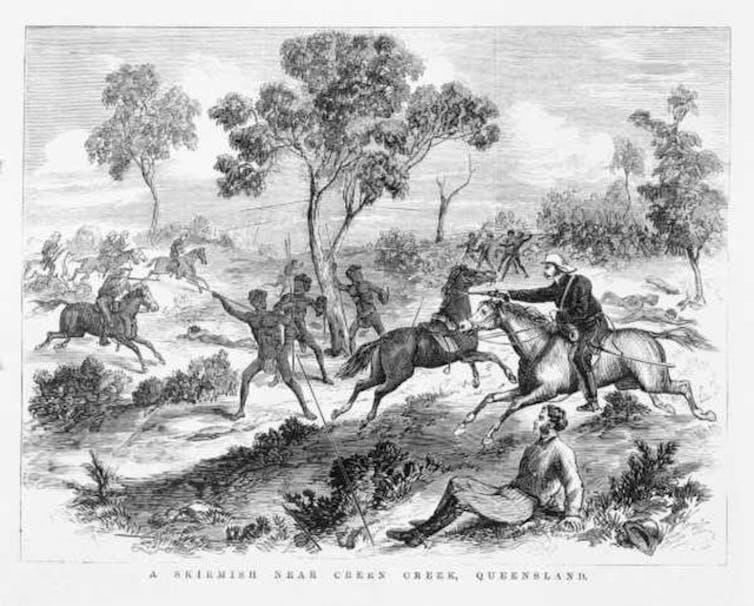

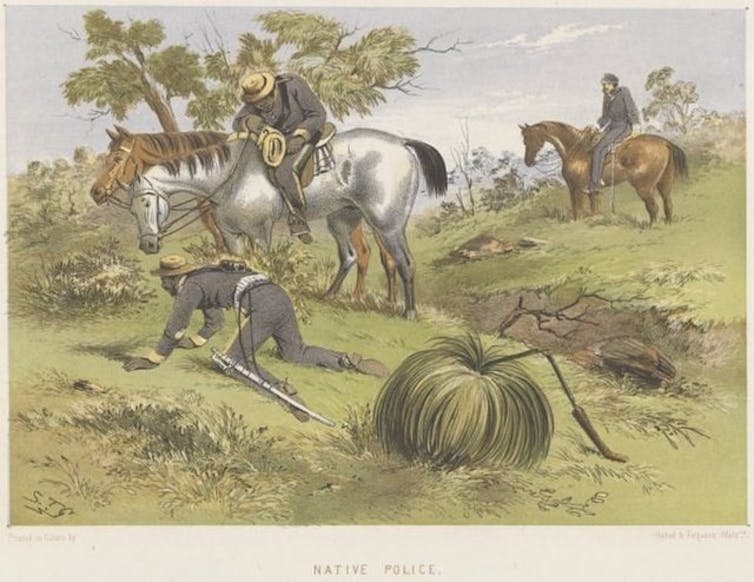

In Federation historiography, Aboriginal people and the colonial violence of their subjugation were mentioned either briefly or not at all. Progress was one theme, soon joined by valour. Gallipoli was interpreted as a nation’s coming of age; the Digger became “the secular everyman”.

Clark is careful not to disdain the popular emotional need that Anzac has continued to address. Anzac would not be a legend if it were not a “vernacular achievement”. It remains labile, its moral implications variously renewed by social movements and political leaders.

Clark is not against History being “sentimental”. Indeed, she distrusts History when it seeks to rise above emotion and judgement. In a chapter centred on Myra Willard’s book History of the White Australia Policy to 1920 (1923), Clark highlights that Federation historiography presented Australia as “white”. By telling her story “diligently and dispassionately”, Willard presented White Australia “as an unproblematic aspiration and ideology”.

This rhetorical effect could not last forever. New readers came to Willard, bringing new questions and anxieties. After Nazism, Clark asks, “was it even possible to regard ‘whiteness’ dispassionately anymore?”

Should history be dispassionate?

What most interests me about Making Australian History is Clark’s presentation of “dispassion” as a problem, for I am more aware of it as a virtue.

While reading her book, I was drafting the following “learning outcome” for a unit I am teaching: “You will be able to speak and write thoughtfully and dispassionately about troubling aspects of Australia’s history.”

My tutor – recently graduated and 49 years my junior – advised me to delete “dispassionately”.

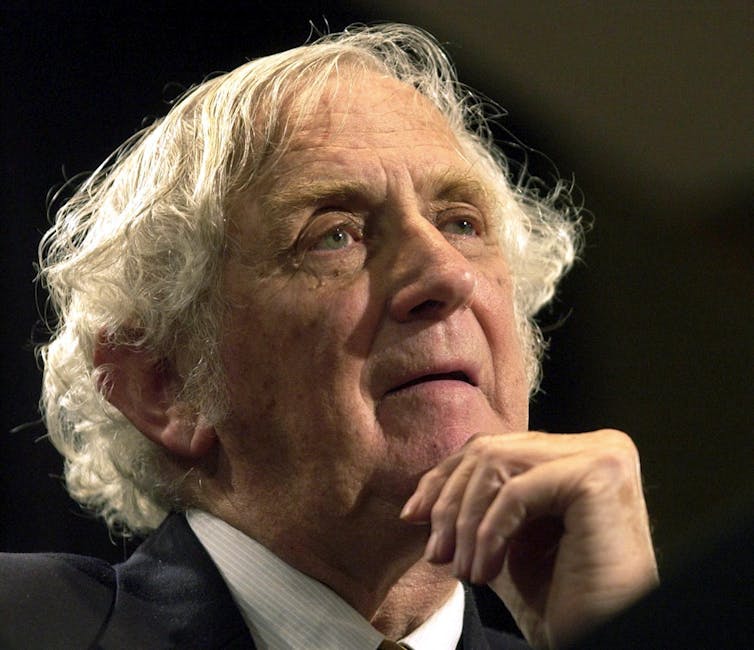

Continuing to read Clark, I soon came across her book’s second example of a “dispassionate” historian: Keith Windschuttle replying to critics of his book The Fabrication of Aboriginal History (2002) that the responsibility of the historian was to be dispassionate, not compassionate.

While I disagree with Windschuttle’s approach to the history of Tasmania, I sympathise with his aspiration to dispassion. Clark does not question his contrasting of dispassionate and compassionate, but I would.

This raises the question of what we mean by historians’ “distance” from those whom they study. Windschuttle’s narrative standpoint was “distant” from both the British and the Aboriginal people – but in different ways. He chose to empathise with the official British view that Aboriginal people were lawless and he trusted the British body count. His critics empathised with Aboriginal people’s defence of their way of life and gave plausible reasons for thinking that much killing was undocumented.

How to empathise with people of the past and see their world through their eyes, insofar as we have evidence of their thoughts, is one of History’s defining challenges. Who to empathise with is also the historian’s methodological decision; it is affected by the historian’s moral and political outlook.

Our empathy for past actors could even be called our “compassion” for them. However, our empathy/compassion is necessarily constrained by the limits of our evidence and by our moral inclinations. Because “we” are not “them”, empathy requires an imaginative leap over a temporal and perhaps cultural distance. Such “distance” includes our retained capacity to dislike or not approve of them.

We can be glad for the gap over which we are leaping when we empathise, because the distance enables us both to understand an action and find it morally disgusting.

The historian then faces a choice whether to state their moral judgement explicitly, to imply their moral judgement by choosing certain words, or to seek scrupulously neutral language so that the reader is not aware whether the historian even feels a moral evaluation.

The problem of distance

If distance affords the historian such choices, then it may be a more useful and necessary quality than Clark implies. If distance is a problem, a necessity and an asset, then it requires a more careful discussion that Clark provides in her chapter on “Distance”.

This is her book’s absent philosophical centre. It is widely agreed that, as a concept within the theory of History, “distance” is a metaphor, not to be pinned down to a single meaning. Clark takes this as permission to deal with “distance” in a way that is so metaphorical as to be unhelpful.

She begins her chapter by admiring Geoffrey Blainey’s insight that great “distance” (between Britain and Australia, within Australia) has profoundly affected every aspect of Australian history since colonisation. She then charts the emergence after World War II of historians’ claims that Australian history is so different from other nations’ that it should not be treated simply as a florescence of British civilisation.

Emboldened by this conviction, white male historians of various political affiliations became a “school” united by two commitments: to an object (Australia), whose characteristic feature was the colonists’ successful struggle with uniquely forbidding “distances”, and to the assumption that their History of Australia “was objective and verifiable”.

In Clark’s usage “distance” becomes the word that staples these two ideas together, so that distance as a fact of geography and historians’ “distance” from their object of study become allegories of each other.

To make her critique of Blainey and his generation, Clark proceeds to load “distance” with negative connotations. She seeks to show that aspiring to be “objective and verifiable” made these historians “distant” from features of the past to which they should have attended, such as “interior lives or emotional subjectivities” and Indigenous people’s experiences of colonisation.

She then suggests that pursuit of the theme of Australians’ distinctive “distance” obscured the many connections between people in Australia and people elsewhere. She points out, for example, that maintaining “whiteness” and institutionalising History as a discipline were not distinctive projects of Australians. These two corrective examples are the fruit of what she calls “transnational history”.

Clark contrasts the “transnational history” practised by her generation with the nation-centred history practised by Blainey’s generation. Her method of argument is to suggest associations between the negative senses of the word “distance” that she compiles.

I admit to finding it difficult to summarise this chapter as an argument, and I hope I have not been unfair, but I found this chapter not so much an argument about historians’ “objectivity” than an extended pun on the word “distance”.

Implying that “distance” was a problem of a particular “school” of Australian History, rather than an inescapable feature of History as a discipline, Clark leaves the reader with no way to decide whether the faults that she finds in Australian History are essential to History or contingent features of the ways some historians have written at certain times.

The following sentence, in the final paragraph of the “Distance” chapter, leaves that question open:

Empirical History had silenced Indigenous archives and muted Indigenous historians in the name of “objectivity”.

I want to know how Clark thinks we can do better. Must “Empirical History” forswear the ideal of objectivity if it wishes to pay full, respectful attention to Indigenous archives and Indigenous historians?

My own view is no. History is not ethically obliged to abandon “objectivity” and we can value dispassion as a way of speaking and writing without forswearing “compassion”, in the sense of empathy for past actors.

Insofar as Clark has written a progressive narrative of Australian History remaking itself, I think that she too leans towards this answer. She sees good possibilities in both “nation-building” and the Enlightenment. Yes, History is porous to nation-building, but this is not necessarily an ethical failure, depending on what kind of nation the historian has in mind.

Indeed, I see Clark as a patriot insofar as she commits History to the project of bettering the ways that Australians live together. Better nationhood, I understand her to say, requires that History help renovate our historical consciousness.

An Enlightenment project

History has been and continues to be a project of the Enlightenment, with its ideas of “truth”, “objectivity” and “progress” – progress not only of knowledge but of civilisations.

The central puzzle of Clark’s book, then, is whether History – a discipline that conquering white men brought from self-universalising Europe – can nurture a sense of the national past that respectfully represents Indigenous Australians as they were then and as they are now. In two of her book’s stories, Clark encourages hope that History can do this.

One is a story that she tells about History: that it is indeed a “discipline”, in the sense that it rewards critical reflection on its modes of rationality. Our ability to historicise the Enlightenment is, in this way, an assurance that we have been formed by it.

Historians feel obliged neither to reiterate the themes of their teachers nor to confine themselves to their methods and sources. The impulse to revisionism is in our disciplinary bones. By celebrating recent revisions in Australian History’s themes Clark embodies this ethos.

The other implicit expression of Clark’s hope in History is that she shows it to have been porous, not only to the noise of nation-building, but also to the susurration of social movements. The most important is feminism, whose transformation of Australian humanities began roughly a decade before the provocation to see Australian history from “the other side of the frontier”.

Feminism demanded the inclusion of previously ignored actors. It showed that “family” was an object of equal importance to “state”. It elevated the significance of certain kinds of evidence, such as oral history, and thus helped to give emotions a reality hitherto reserved to other more “material” factors.

Feminism forcefully raised the question of “standpoint”, an idea for whose sympathetic reception many historians had been primed by reading the English philosopher R.G. Collingwood.

Clark’s 35 references to feminism attest to its reformative influence on her discipline and on her. History would not be as receptive to the remaking that Clark has plotted had it not begun to take up what feminism offered.

This article is republished from The Conversation (opens in new window) under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (opens in new window) appeared on March 21, 2022.