"Not another Bankstown": Cultural fears over place

A Lunchtime Seminar Series Summary

By Ryan Al-Natour

29 June 2011

On May 3 CCR HDR candidate Ryan Al-Natour spoke at the third session of the Lunchtime Seminar Series 2011, presenting ‘“Not Another Bankstown”: Cultural Fears Over Place’.

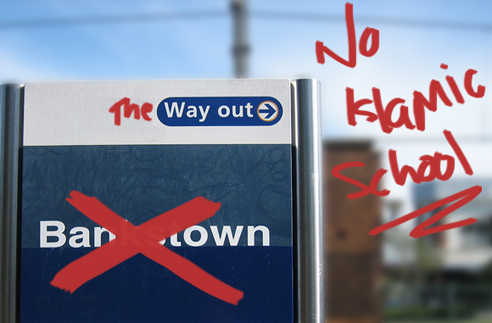

In May 2008, the Camden Council decided to reject a proposal for an Islamic school in Camden, which is located in the south-western greater Sydney fringe. Surprisingly, only 200 people attended the Council meeting, even though prior rallies against the school attracted thousands of protestors. With the Cronulla riot taking place only 2 years prior to the school controversy, news reports had shown similarly heated scenes of anti-Muslim protestors sporting the Australian flag, and chanting ‘Aussie cheers’ that are usually heard at international sporting events.

At the first anti-school rally, thousands of local residents gathered to voice their opposition against the proposal. The rally organiser asked for a show of hands of those supporting the proposal in the crowd of thousands. Only two people raised their hands, to which protestors around them yelled ‘Go back to Bankstown’. Those two residents were ‘locals’, yet their support for the school marked them as ‘foreigners’ to the Camden landscape, as they were vilified with a similar slogan usually told to particular ethnic minorities: ‘Go back to where you came from’.

Throughout the controversy, descriptions of ‘another Bankstown’, ‘mini-Bankstown’ or ‘little Lakemba’ frequently came up among some opponents of the school. In the risk of becoming ‘another Bankstown’, some residents were concerned that an established school would transform the Camden vicinity into ‘another Bankstown’.

So, what about this ‘another Bankstown’? As it operated throughout the school controversy, ‘another Bankstown’ was a prediction of Camden’s future with an Islamic school. For some opponents, it was a process of de-localising and becoming foreign. For others, it was a place flooded with and controlled by Muslims. It was also a place that was fashioned as ‘city’ and ‘ethnic’ simultaneously. And for some opponents, it was a place where crime was rife.

In my research, I point out that ‘Another Bankstown’ was an imagined place, often a frightening ethnic ghetto was fashioned by the opponent’s specific concerns. If the opponent was concerned with maintaining ‘rural’ Camden, ‘Another Bankstown’ was a ‘city-area’. If the opponent was concerned about preserving the area as ‘white’, ‘Another Bankstown’ was fashioned as a place where whites were not the majority. If they were concerned about public safety, ‘Another Bankstown’ was conceptualised as a crime infested zone. In each case, ‘Another Bankstown’ was fashioned as the antithesis of Camden as it exists and as it is imagined today. These various constructions of the contemporary ‘ethnic ghetto’ demonstrate how it floats between the very different, yet related, entangled fears of the school.